When I studied film this is one we were forced into watching because it exemplified the qualities of melodrama. Now, of course, I can’t use the word without thinking of the film, of Dorothy Malone stroking that oil rig, to be precise, and of Robert Stack clutching his gun and collapsing out the door. My first watch was marred by “that woman isn’t as beautiful as they want her to be,” and my second watch was marred by “I can’t believe it was Lauren Bacall the whole time. She has the voice of a man too.” Though I’ve admired photos of her before, perhaps it was from days before her features grew sharp, I’ll have to see some of her earlier films, find out what all the fuss was about. The film didn’t do a thing for me six years ago–I thought it was purely an example of a genre, nothing more. Surprise to see Criterion released it, and the reason why: this was Sirk after being freed from the Hollywood constraints, to achieve his own vision. The Cahiers du cinéma crowd recognized it as being profound, so I paid closer attention to colors, though I haven’t begun understanding space, nor being quite aware of cuts and camera movement. But I know what moves me: the scene in which Dorothy Malone is dancing wildly in her bedroom, as her father ascends the stairs, and then collapses, rolling down them again, and Lauren Bacall realizes something’s wrong. The new films are so quick to toss in a sex scene–my only complaint of these new Scorsese films–and one begins to wonder if there’s just a store of them you can buy on the cheap, and plug in to your film. Here’s a film that, even in its overt sexual overtones, remains something children could watch–unless you don’t want your children watching films with alcoholics and gun violence–something that would make their hearts beat more quickly, and yet they wouldn’t know why. So it’s a melodrama as a screenplay, but it’s an exercise in subtlety as concerns its insidious sexuality, and however one’s emotions are meant to be bombarded, mine tend to remain clear during this film, delighted by the colors and movement. Now, if only I could tie in the intellect…

film: Berkeley: For Me and My Gal (1942)

Little known secret: more than anything I want to dance. Astaire, in Holiday Inn, I didn’t know what life was until I saw him move, and then Gene Kelly in American in Paris. Well…there’s no magic anymore, so, what have I? India. I will simply mention my one observation on this film, something very funny. If you’re familiar with films from this era, then you’ll know that what would seem to be the climax always comes when it seems reasonable, and then the film stretches on for another hour. In that “climax” here, in less than ten seconds the film turns from a reasonable Hollywood romance into blatant government propaganda as Judy Garland becomes enraged that Gene Kelly has temporarily dodged the draft by closing a door on his hand. She shivers angrily and says she never wants to see him again. Okay. And don’t forget to buy war bonds.

Judy Garland’s lips are amazing. I don’t know if I could kiss them except in the same way that I might shoot lighter fluid–just to see what happens. They exemplify precisely why film was created: to capture the human lips.

film: Feuillade: Juve contre Fantômas (1913)

I was wrong about the Fantômas series–this film is fantastic. What shines through, above all else, Feuillade’s level of confidence. The first in the series, which bored the hell out of me, had very little movement, scenes were drawn out, stereotypical mime pageants, and it felt like silent theatre. Juve is a bumbling detective who gets lucky in catching Fantômas, who seems to be a passing clever criminal. [spoiler begins here] In the same year as the first film, this was produced, and all is different. Juve takes action as he and Fandor show some slight ingenuity, doing things like climbing into barrel and rolling themselves down to the ocean to escape a fire–indeed, the sets are greater. There’s humor, as Fantômas is arrested while at a party, escapes the police, and goes immediately back to the party. There’s more of the characteristic attempts at murder, including an enormous snake, whose guts we get to see. And the end is shocking–as Fantômas blows up an entire police force, including the main characters, and we’re left wondering what the hell happened. It takes confidence to do all this–because it is not only Fantômas or Juve’s ingenuity, but Feuillade’s, and although the camera remains still in all its shots, there are many, many more shots, whose lengths are beginning to take on the pace and movement of the film. If only I could understand all the inter-titles! After seeing four or five of his films, I can say that this is the one that makes me a fan of Feuillade.

film: Curtiz: Casablanca (1942)

Lately it’s becoming more common that I learn my body can do all sorts of neat things. Usually these things involve intense physical discomfort and/or pain. As the band struck up “As Time Goes By” and the screen faded, I found myself with a smile I’ve never smiled before, one that I cannot recreate, one that I’ve never felt in all my life and perhaps would not even recognize now. I wonder what it looked like–though I wouldn’t have seen it even in a mirror, because my eyes were teary. The ending makes the film; I guess that’s why I knew it before it showed up; how many endings can be so unhappy, yet so wonderful?

This picture of Casablanca looks like a running horse to me:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Casablanca_7.58684W_33.56662N.jpg

and “La Marseillaise” I now think is the prettiest, strongest, national anthem I’ve ever heard.

film: DeMille: The Cheat (1915)

I would expect that my introduction to a director whose name I’ve so long known I’d be far more impressed. Or impressed at all. As it is, I have almost no recollection of this film at all. And I’m pretty sure that I watched it just this morning. Now, let’s see–aside from DeMille, it was significant because it actually had an Asian man as its villain. And further, even without speech the man played the role of the brilliant-and-kindly-seducer-turned-wicked-rapist very well. And when he brands his victim I was just thankful that the villain, who could have been anybody, was not made Jewish, despite a heavy Shylockian quality. What is clear, though, is that silent films will necessarily fail when trying to portray an exhilarating courtroom drama–but, despite this, the protagonist gives a stellar performance during the bit where she rips her shirt off. If the shirt stayed on, I’m not sure how good the performance would be, but it was enough today. Though very boring.

film: Hitchcock: The 39 Steps (1935)

I was thankful that The 39 Steps was not actually a thriller, not in the later Hitchcock sense of the word. Of course it had many of his later elements, and much of his humor, and most notably: an otherwise anonymous woman opens her mouth to scream, and a train whistle blares forth, from the next shot. These are the sorts of tricks he revisits. And with everything tying together so nicely, and a nice implied love at the end, in my mind this film illustrates how Camus’ The Stranger could have been sweetly resolved. But so it goes, the difference between existentialists and everyone else.

show: Pippin

From the first I’ve maintained that the ending is tragic, and my friends all disagreed, saying it was a happy ending, after all, it’s a comedy, and he ends up with a happy marriage and escapes what would amount to murder. The ending is devastating. When I first saw this I cried, and when I got my hands on the soundtrack, I cried, and finally I couldn’t listen to the last track anymore, and watching it now, five years later, I still cry. Perhaps it’s devastating to a certain sort of person, a person who is still idealistic, and whose idea of the future is only one of brightness and glory, though of nothing definite. And there are all the walls, and the practical side of life and all those people who abide by it, who make utopias impossible, who make dreams remain dreams. This is about the only answer we grow to have, that is suicide, and ultimately Pippin refuses to kill himself, not, as my friends believe, out of recognition of true love or of the joy in a simple life, but out of fear and cowardice, taking that chorus he sings throughout the play “rivers belong where they can ramble, eagles belong where they can fly,” and instead changes to “i’m not a river, or a giant bird that soars to the sea.” He gives up his dreams and settles for what he sees as the only alternative to death.

The play is self-aware from start to finish, and we are never allowed to forget that we are watching a performance, with makeup and actors and lines and so forth. And even time itself is flexible when we find that characters can easily be brought back to life, with little consequence. But what throws everything off is when characters begin transcending the play, when they take on lives of their own, and if Catherine is falling in love with Pippin after the death of her husband and the difficult raising of their child, well, at what point did the play begin? And when the script is entirely disregarded, and characters begin making their own decisions, we aren’t sure if they are characters, or real people, or where the stage begins and ends, or what is true.

I expected the performance, which has the same actors as the soundtrack, to follow the soundtrack note for note. Wrong. The first words sung, “join us,” and the rest of the song, is mostly sung in the pocket, deeply. When Ben Vareen does it, it’s artistic interpretation–which seems a bit incorrect in a musical–but when everyone does it, then I grow to wonder how exactly the soundtrack was recorded, all its differences. The soundtrack, released on Motown, sounds like 1972, that is, it fits alongside the sound of James Taylor’s home studio, the brief earthiness of Chicago, and all the other organic sounds of that short era, after the Beatles led recording out of the dark ages but before over-production became the standard. It’s a compressed sound, but it feels familiar. Generally, the vocal performance on the soundtrack is far better than it is live–and there’s no reason it should be this way, given the examples I’m thinking of don’t involve heavy dancing. Catherine’s has a seductive innocence on the album, but much more self-assurance (and vibrato) in the live performance. This also goes for Pippin–whose soundtrack voice contains multitudes, whose performance voice needs the dancing alongside it. Of course, the choreography is stunning, especially Ben Vareen, I could watch it endlessly, and it’s perhaps Fosse’s influence that gives the play its morbid quality, as opposed to the optimistic Godspell feel of Schwartz’s first musical and subsequent work.

This is a play for young people, for people who still believe in the impossible; when I first saw it, it was all I thought about for many, many months, working at the dry cleaners, thinking about Pippin, and it has not failed me yet–though I wonder if the day will come when I have grown mature enough that I will criticize the play for all the things I once adored.

film: Feuillade: Les Vampires, Le Cryptogramme rouge (e3, 1915)

Finally, the first evidence of burning sexuality in film. 1915. The gang sits backstage, and one of the men walks across the room, looking like Marlon Brando, very self-assured, he turns around and whistles, and a woman follows his path and right as she reaches him he roughly grabs her the hair atop head and pulls her down, toward him, spinning her and she throws her head back as she pulls into his arms, and then; and then, clutching her neck with one arm, they step across the room and begin dancing to a waltz, violently he spins her, grabs her, pulls her down and back up, and when she puts closes her hands behind his neck, he grabs hold of her hair, and they dance in circles, heads pressed close together, more dips, and then she jumps, he holds her waist, and spins her round and round, her knees bent, her body as if its lying on a bed, and then when she lands he spins her and lets go, and it looks like he has just struck the winning blow, and shakes his hand outward, free of the dance, and then quickly walks away. Now I can say a silent film has held me captive.

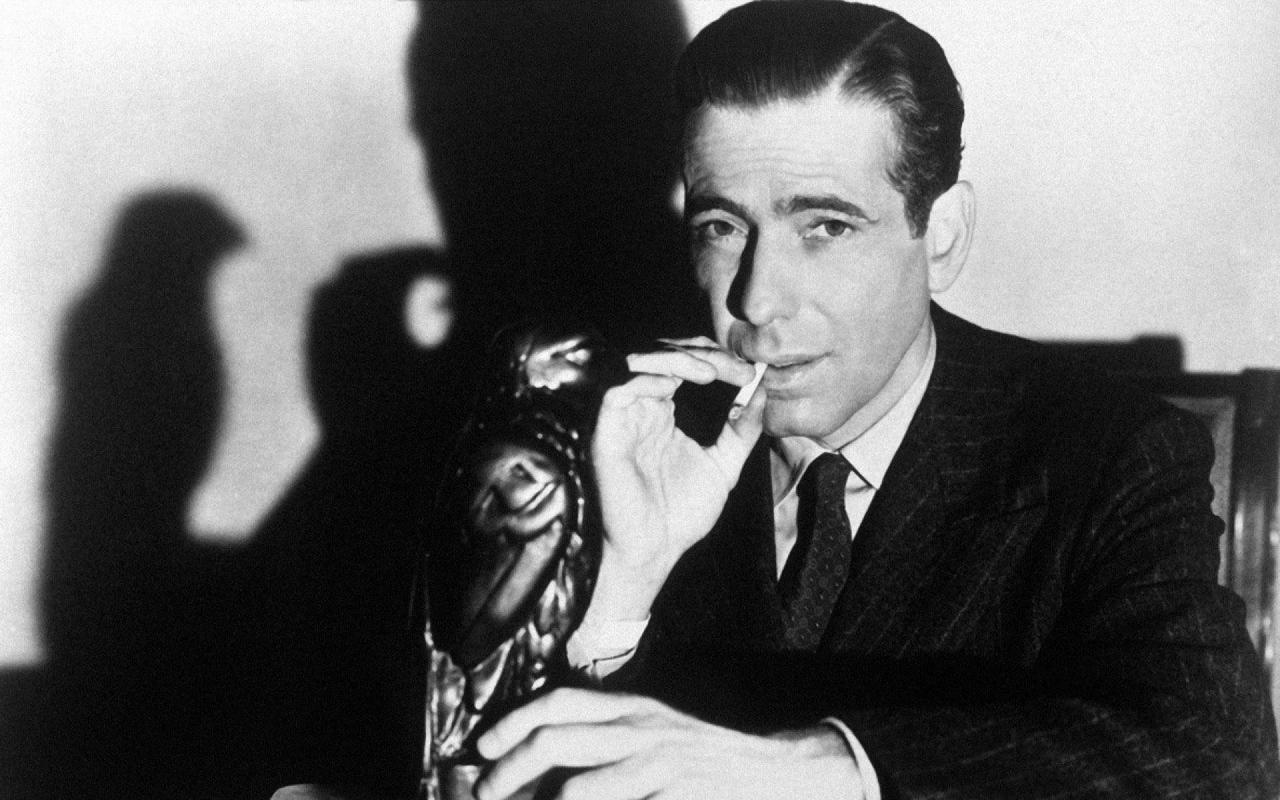

film: Huston: The Maltese Falcon (1941)

If you didn’t know, I studied film during my first year in college, and finding myself, after one year, too emotionally unstable to continue its pursuit, I switched to studying something else. I didn’t watch another film until 2007–and this was it. Watching it, I suddenly understood many things I hadn’t as an artsy film student trying to “get” Godard’s À bout de souffle, and so I decided I’d watch the classics so I could understand French New Wave. And then I figured, well, I might as well just take things from the beginning since the popular medium began less than a century ago, and that explains why I’m watching all these silents. It’s not because I have a passion for silent film…I’m actually more fond of Bergman and Godard. So…here we have the beginnings of this project.

If you didn’t know, I studied film during my first year in college, and finding myself, after one year, too emotionally unstable to continue its pursuit, I switched to studying something else. I didn’t watch another film until 2007–and this was it. Watching it, I suddenly understood many things I hadn’t as an artsy film student trying to “get” Godard’s À bout de souffle, and so I decided I’d watch the classics so I could understand French New Wave. And then I figured, well, I might as well just take things from the beginning since the popular medium began less than a century ago, and that explains why I’m watching all these silents. It’s not because I have a passion for silent film…I’m actually more fond of Bergman and Godard. So…here we have the beginnings of this project.

Okay, so now I’ve seen the whole film. Though not necessarily in the correct order, I’ve seen it, and I’ve begun to pick up on what the defining traits of Sam Spade are–though, if I mean Humphrey Bogart, then I will know after having seen Casablanca. I was prepared this time around to not understand the characters because they speak too quickly, so I kept subtitles on, and I had the pleasure of being able to rewind and watch bits multiple times (Sam Spade pulls the guy’s jacket down over his arms, and grabs the guns from his pocket–how’d he do that?) Now I’ve seen detective films from three different decades: Fantomas, in which Juve doesn’t really have much charisma, so we find ourselves cheering for Fantomas, as heartless as he is, just hoping that his victims will end up alright as often as possible. Nick Charles [The Thin Man], he’s got the charisma, and he’s got the smarts. Juve tends to have things go smoothly, Nick Charles would take a smooth ending and find a reason why it’s entirely wrong, and sneak off to make things more exciting. But for all his quips, and however quick he is in punching out his wife when he determines she’s in the line of fire of the gun he’s about to provoke, he’s still drunk for the whole movie, and always seems but hairs breadth away from being badly damaged. But Sam Spade, he seems like he invented smart one-liners, and he’s so easy with them that he condemns others for using them poorly. Everyone’s against him, and he himself is fallible and a bit immoral, coldly working for money and sex, threatening and extorting and earning our support all the while. He reads people, he reads situations, and one wonders if he’s acting, ever. So, now it’s clear where Godard builds his Michel–who uses Bogart’s character to no good, and begs the question, is there a normative morality? One character modeled on the other, yet with tragic results, despite romantic plots. Perhaps that’s the division between Hollywood and Godard, or of movies and life, or an observation that Sam Spade is only himself when in his home environment, when he knows the tricks of getting through locked buildings and the DA’s by name. Would Sam Spade kill a cop? Perhaps, but he wouldn’t hide afterwards.

film: Feuillade: Les Vampires [e2] : La Bague qui tue (1915)

Midway through a scene, a shot, that looked almost identical to one from Fantomas. The film was carried heavily by letters and newspapers, as in Fantomas, and…surprise, the same director, Feuillade. I could not get my hands on episode 1, so I began with 2, and it was short enough to maintain some of my attention, though I don’t know how well it will continue to do so. But–I’ve turned back on my earlier plan to stop watching things that I know I’ll hate. Why? Well, because this director and his Fantomas and Les Vampires series were influential on the surrealists, whose work I’m trying to read. I also don’t enjoy Buster Keaton–and he was influential on them. But, one watch, and that’ll be all. If I didn’t enjoy Fantomas and yet I’ve had so many observations and comparisons later based on it, then I’ve achieved my task. If Der Student von Prague is by the same director as Der Golem, and if it highly influenced the horror genre…well, I should keep going.